Malcolm Gladwell’s article “Small Change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted,” brings the slacktivism, social media for social good or evil, strong and weak ties, and organizations vs networks debates to a mainstream audience. He tries to make the point: “Social change has been happening before the creation of Twitter four years ago” but disappoints. Anil Dash says it is wildly anachronistic to think that the only way to effect social change is to assemble a sign-wielding mob to inhabit a public space or as he says “Take A Bath Hippie.”

The post initially caught my eye because there was a quote from Jennifer Aaker and Andy Smith, co-authors of The Dragonfly Effect (I’m giving away a copy). I posted a link on FB page and it prompted quite a discussion from nonprofit folks. There have also been some good critiques of the article that I’d like to highlight here:

Article Isn’t Well Researched: There Are Good Examples Out There of Folks Using Social Media for Activism

Nancy Scola at TechPresident, in a post called, Malcolm Gladwell Goes Searching Twitter for 60’s Activism

Rather than comparing Woolworth sit-ins to the much-hyped Twitter Revolution, finding the latter coming up wanting, and stopping there, Gladwell might have given some space in the New Yorker to dig a little deeper to find examples of folks using technology to organize in intriguing, successful ways. The examples are there, too. The Obama campaign, for one. How the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America is using the web to bring back together their band of brothers and sisters. The aforementioned Greater Greater Washington. They may be few, but it’s still early. We’re only four years into the Twitter era, after all.

My co-author, Allison Fine and I found many great examples of successful activism using these tools as part of multi-channel campaigns in our book The Networked Nonprofit.

Gladwell’s assertion that social movements are based on tight ties and online efforts on, say, Facebook, are participatory efforts based on loose ties is simply not true. When one looks under the hood of a successful activism efforts, as Beth and I did for The Networked Nonprofit, whether part of movements or campaigns, they have a combination of initially tight ties, someone does have to drive the train, and loose ties, others have to join the effort for it to take off. In addition, all of the successful social efforts in the connected age happen both online and on land – see Moms Rising’s onesie campaign, Surfrider’s advocacy efforts, the Humane Society’s Spay Day efforts on Facebook and on land.

He also makes a false distinction between online/offline or as Allison and I have called it “online and onland” activism. She Jillian York’s critique.

The Tools Don’t Create Strong or Weak Ties, Stories and People Do

Lina Srivastava in her post, “Welcome to the Debatem Malcolm” points out that this isn’t the tool that creates the strong or weak ties:

The way a campaign engages empathizers, influencers and activists– whether based on what Gladwell notes as weak or strong ties– is really more a matter of strategy– issue identification, context, methodology, desired action, outcome, etc. Use and application of digital tools is a tactical concern– important, but not the endpoint. And so Gladwell creates a false distinction when he claims it is the nature of the tool that creates strong or weak ties. I would argue it’s the content and the context that determines and strengthen ties. The medium is not the message here.”

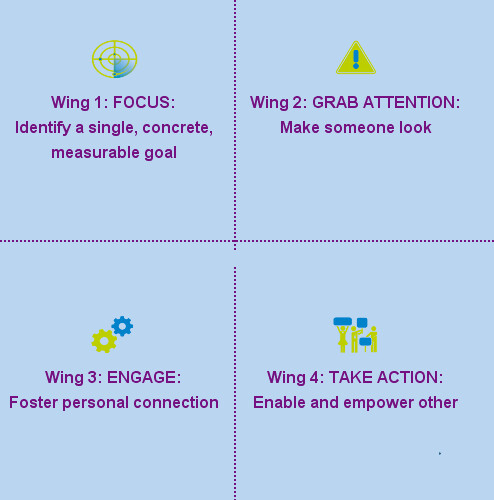

One of the things that I love about Jennifer Aaker and Andy Smith’s new book, The Dragonfly Effect is that they offer a lot fabulous frameworks for thinking through the points that Lina mentions above – the content and context strenthens ties.

Jennifer Aaker, co-author of The Dragonfly Effect, posted on the FB thread,

As Malcolm suggested lowering the bar, making it easier for people to participate, is one mechanism at hand. But there are other mechanisms at work too. The level of motivation increases (which increases participation, independent of ability). Where does motivation come from? It is generated partly from the story, and the social network that enables that story to be told. And it is generated partly by social cues. And where are you likely to fine more personally relevant social cues than embedded in a network of your closest friends and contemporaries? There are stories that people want to share and stories that people want to hear. Social media allows the people who have stories but no resources finally have their stories heard.

Gladwell Got It Wrong About Strong and Weak Ties

Gladwell argues that real social change occurs when strong, rather than weak-tie networks, organize hierarchically, rather than in a de-centralized network structure. Many of us in the weeds disagree. This well-written post by sociologist Zeynep Tufekci spells out why Gladwell missed the point about strong and weak ties.

I will make two main points in this post. One, the key issue facing activists who wish for real social change is the mismatch between the scale of our problems (global) and the natural scale of our sociality (local). This is a profound problem and more, not less, social media is almost certainly a key element of any solution. Second, the relationship between weak and strong ties is one of complementarity and support, not one of opposition.

The first point is one is the thesis of our book, The Networked Nonprofit – in short that the social problems are so complex that single nonprofits can’t solve them along and need to work more like networks. And certainly, I agree that social media plays an important role.

I agree with the second point about strong and weak ties complement each other – they don’t work against each other. Here’s how it is explained:

Strong versus weak ties should not be seen as opposites but rather as supporting and complementary dynamics. One key point is that Internet bolsters strong ties directly and indirectly. Directly, because Internet allows for more frequent, trivial “ambient” communication and that is the bedrock of strong-tie formation. All those tweets about what you had for breakfast that everyone makes fun of? A lot of research shows that if you record ordinary people’s conversations with their close friends and family and you will find that this is exactly what they do – talk about the mundane rhythms of life. Current structures of suburbia, distant homes, moving for jobs, smaller families, etc. all make it harder to engage in that kind of daily interaction – and weaken our communities. The Internet is the opposite of these processes: suburbs took us away from other people and locked us into houses; the Internet opens a door from the house into potentially shared places.

Nancy Scola has a post called “Strength of Tweet Ties” where she provides some examples of how this works through her professional connections. She learned of the Zeynep Tufekci from a tweet by Ruby Sinreich who she has only met in person a handful of times, but follows her on Twitter. Nancy goes on to describe the relationship as neither weak or strong ties – and absent from Gladwell’s piece. Nancy suggests that are relationships and interest are no longer defined by geography anymore, whether we’re talking about news or our political interests.

“The two interactions — infrequent passing interactions offline and our near daily reading of each other’s thoughts online — seem, to borrow and slightly twist a phrase from Tufekci, “one of complementarity and support.” We have a good deal in common, even if we live hundreds of miles apart. That’s a sort of relationship that seems neither particularly strong nor particularly weak, but one that’s absent from Gladwell’s take on the nature of modern activism.”

Alexis Madrigal in his post Gladwell on Social Media and Activism also questions the black and white description of strong/weak ties that Gladwell states.

First, a smaller quibble. Gladwell defines Twitter like this, “The platforms of social media are built around weak ties. Twitter is a way of following (or being followed by) people you may never have met.” But the thing about Twitter, at least for me, is that I *end up* meeting the people that I interact with most closely. Twitter acts as a kind of human recommendation engine in which I am the algorithm. In person, I’ve met Clay Shirky himself, Tim Maly, Robin Sloan, and at least 10 more — and I’ve edited dozens of folks that I know exclusively through the service. What Twitter lacks in corporeal contact, I think it makes up in longevity. I’ve been watching some people’s minds work on the service for years. Every day I see their faces in my feed. To label these weak ties is just inaccurate. And it makes me wonder, can’t we know people through their writing? Is face-to-face contact the only way to build strong ties?

Marc VanBree talks about it from his experience as a free agent raising money for disaster relief in Nashville.

When I conducted my #floodofsupport experiment, the results could have been construed as somewhat disappointing. But I did not send an appeal to friends and family, I purely relied on my Twitter network. That was the point. Even then, those who donated were definitely contacts with whom I had more in-depth conversations. So yes, if you build a campaign to solely rely on weak ties, it seldom leads to great involvement and thus could be construed as disappointing.

And a quick take from Aaron Lester from the Nonprofit Quarterly rounds it out.

Top Down Command and Control Organizations Are The Only Way Social Change Happens (WRONG!)

Gladwell is saying that working as networks can’t effect social social change.

The drawbacks of networks scarcely matter if the network isn’t interested in systemic change—if it just wants to frighten or humiliate or make a splash—or if it doesn’t need to think strategically. But if you’re taking on a powerful and organized establishment you have to be a hierarchy.

Again, this isn’t a black and white – organizations versus networks. I am reminded of the PDF 2009 keynote from Mark Pesce about the Tower VS Cloud. He talks about the strengths and costs of the hierarchy (organizational structures) and the cloud – and that the two forms are not compatible. But nonprofits need to focus on the interfaces that connect the hierarchy to the cloud. (Allison and I wrote a whole chapter on this in our book, the Networked Nonprofit, called Social Culture)

In the 21st century we now have two oppositional methods of organization: the hierarchy and the cloud. Each of them carry with them their own costs and their own strengths. Neither has yet proven to be wholly better than the other. One could make an argument that both have their own roles into the future, and that we’ll be spending a lot of time learning which works best in a given situation. What we have already learned is that these organizational types are mostly incompatible: unless very specific steps are taken, the cloud overpowers the hierarchy, or the hierarchy dissipates the cloud. We need to think about the interfaces that can connect one to the other. That’s the area that all organizations – and very specifically, non-profit organizations – will be working through in the coming years. Learning how to harness the power of the cloud will mark the difference between a modest success and overwhelming one. Yet working with the cloud will present organizational challenges of an unprecedented order. There is no way that any hierarchy can work with a cloud without becoming fundamentally changed by the experience.

The last section of his essay talks about the cloud, tower, and storm, elegantly pushing the metaphors.

All organizations are now confronted with two utterly divergent methodologies for organizing their activities: the tower and the cloud. The tower seeks to organize everything in hierarchies, control information flows, and keep the power heading from bottom to top. The cloud isn’t formally organized, pools its information resources, and has no center of power. Despite all of its obvious weaknesses, the cloud can still transform itself into a formidable power, capable of overwhelming the tower. To push the metaphor a little further, the cloud can become a storm.

Gladwell’s essay casts argument into black and white and ignores the shades of gray. At best, it was intentional to spark debate. At worse, it wasn’t a well researched piece.

You can go ask him yourself at 3 PM EST Today during a Chat hosted by the New Yorker.