I’ve been closely following the use of social media for activism the Arab world given the project I’m about to begin work on at the end of the February. Jillian York, a US-based blogger who free expression, politics, and the Internet, with particular focus on the Arab world and also write for Global Voices (see their special coverage of the Egyptian protests here. ) Jillian has been asked this question a lot in the last few days by journalists, “How are protesters in Egypt Using Social Media?” to help understand the relationship between online and offline protests. As Jillian points, out there is a danger of slanting the resulting story so it either over-hyped or insulting. As she says, “Go one way, and you risk overstating the influence, go the other and you’re dismissed as assuming individuals in the Arab world incapable of leveraging social media tools for organizing.”

Jillian’s take on the coverage:

To be honest, so much of the rhetoric around the use of social media in Egypt and Tunisia makes me want to scream — folks act like these American tools just dropped from the sky like humanitarian food rations, set to save the people from their (American-supported, natch) dictators.

As Sami Ben Gharbia so eloquently noted on Al Jazeera’s Riz Khan program last week, these networks have existed for a long time. Are they enhanced by social media? Of course, and I’m sure Sami would agree. But when did we go from referring to social media as a tool to calling it the catalyst of a revolution?

I will leave this with a final thought cribbed from Ethan Zuckerman, who wrote last week: “Tunisians took to the streets due to decades of frustration, not in reaction to a WikiLeaks cable, a denial-of-service attack, or a Facebook update.”

Yesterday as I was driving, I heard an interview on NPR’s Talk of The Nation with Jillian answering that same question in the context of the Egyptian Government shutting down Internet access and as the Washington post reported, “an audacious escalation in the battle between authoritarian governments and tech-savvy protesters and a direct challenge to the Obama administration’s attempts to promote Internet freedom.”

The New York Times reported on the use of social media and protests suggesting that Egypt’s government was afraid of the power of social networking tools. The article goes on to explain that while repressive regimes around the world may have fallen behind their tech-savvy opponents, many governments have begun to climb the steep learning curve and turn the new Internet tools to their own, antidemocratic purposes.

The countertrend has sparked a debate over whether the conventional wisdom that the Internet and social networking inherently tip the balance of power in favor of democracy is mistaken. A new book, “The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom,” by a young Belarus-born American scholar, Evgeny Morozov, has made the case most provocatively, describing instance after instance of strongmen finding ways to use new media to their advantage.

If you check out the Twitter Hashtag for #jan25 you will see many different tweets in both English and Arabic and as of this morning some Tweets protesting the government censorship by blacking out words in the tweet and protests in NYC. Perhaps my colleagues at SMEX Beirut has this in mind when they re-posted this request, “Free World: Speak Up For A Free Egypt,” a call to action to the world from Egyptian activists – originally posted here from @manal and @alaa. (And, if you’re not on Twitter, you can go retro by picking up the phone and calling the Egyptian Embassy and telling them what you think)

The #jan25 Twitter hashtag also has examples of the how social media is being used as well as State Department’s Arab Twitter Diplomacy. There are a few issues with trying to follow the issue directly via the hashtag. It is a firehouse, uncurated list. How to contextualize it? Also, since I don’t speak or read Arabic and it is difficult to translate from Twitter, how can I figure out what’s going and even participate in the discussion?

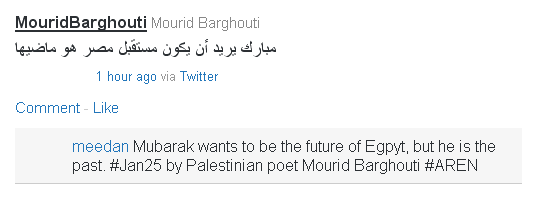

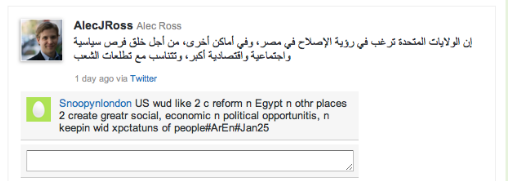

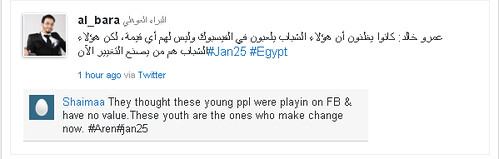

Meedan has set up a stream of curated tweets from the #jan25 hashtag and is translating them into both English/Arabic. So for example, now I can see what State Department was tweeting in Arabic. According to Ed Bice, the short term goal is to just make sure that information is flowing between language communities and the longer term goal is to network these communities.

So, using this curated list, you can begin to get a better understanding of different views on this from other places in the world. For example, what is being tweeted about the use of social media.

Right now there is not anyway to crowdsource translations and attach a translation to Tweets. Meedan is working with a tool that was intended to annotate tweets called Curated.by – an elegant workaround. What is needed, perhaps, is a Twitter Annotation project to facilitate translation of languages. What this can do is prevent language from being a barrier to participate or follow a social change through social media in places around the world.

In the meantime, if you want to help translate the tweets, instructions are here and here.

Update 1/30: Enough about social media and protests. This morning’s New York Times reports that the Obama administration is pressing for change in Egypt but has stopped short of calling for Hosni Mubarak’s resignation. My social media colleagues in the Middle East, Jessica Dheere and Mohamad Najem, co-founders of SMEXBeirut have written an open letter on their blog calling for a clear statement from President Obama and Secretary Clinton encouraging Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak to step down. They feel reform is not enough.