Over the past two years, as part of my work as Visiting Scholar for nonprofits and social media at the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, I have had the opportunity to participate in The Network of Network Funders (NNF) , a community of practice for funders who are intentionally investing in and working through networks. The focus has been to develop practice and share insights on networked effectiveness. I’ve had the pleasure working with Diana Scearce, from Monitor Institute, who has been facilitating and weaving this network.

There are several learning cohort groups, including one on better understanding network impact. Recently, I presented a high level overview of crowdsourcing, including examples from the lens of funding and doing. It was good opportunity for me to look back at the crowdsourcing chapter in our book, The Networked Nonprofit, and update the examples and thinking. The presentation was followed by a discussion about how one might evaluate efforts to engage crowds. What do you track? What domains of impact should be considered (e.g. impact of the crowd-produced product, impact on the crowd / community)?

Crowdsourcing is defined broadly as:

The process of organizing many people to participate in a joint project, often in small ways. The results are greater than an individual or organization could accomplish alone.

Last month, I heard a talk by author Jonathan Salem Baskin about his soon to be published book, “Histories of Social Media.” The book looks at social media concepts and ideas, asks is this really new? The technology tools certainly are, but history provides a context for every behavioral quality of new media. Therefore, my new question in presentations about social media has been to ask: Is this new?

Collective activities are not new to social media. The Audubon Society organized the first Christmas Bird Count to inventory all the birds in the Western Hemisphere in 1900. But now using social media enable the Society and (anyone else) to increase this activity with less effort and less cost. Over a century after its inception, over 52,000 people in 1823 places across 17 countries participated in the Christmas Bird Count – using email, web sites, and social media tools. Social media accelerates the crowdsourcing process – it can happen faster. Crowds are powerful, but you must know how to effectively use them or it can be more work. The key is breaking down the tasks into bite-size pieces and engaging crowds in the process.

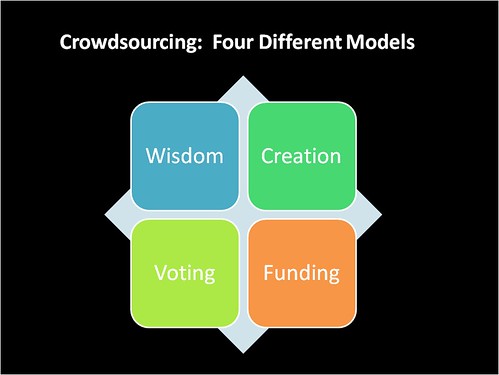

There are four different models of crowdsourcing activities: wisdom, creation, voting, and funding. There’s isn’t one best way to do it – and many organizations use a combination of these models to meet their objectives. Social media tools for engaging and capturing the work of crowds include: wikis, custom platforms or web sites that facilitate voting, rating, giving feedback, adding content, or funding. And, you can use social media tools such as Twitter, Facebook, Blogs, to support engaging crowds to participate in the activity.

Here’s an overview of the different types and some examples for each in philanthropy and doing.

(1) Creating collective knowledge or wisdom

A group of individuals has more knowledge for solving a problem than any single individual. Collective intelligence creates a quilt of knowledge that many people can distribute.

Public Insight Network in Minnesota is a network of 100,000 people who help make Minnesota Public Radio News by sharing their observations, insights, and experiences with reporters and editors who may share these insights through a story or on the web site. The measures of impact for this project include diversity, deeper and more relevant reporting, and better connection with listeners.

Maine Health Access Foundation did an experiment on Facebook, including it in its channel to promote a funding opportunity but also posted the initial letters of inquiry on their Facebook page to get feedback. The measure of impact is to determine whether the comments and feedback strengthened or improved the final proposal.

Crowdsourcing for knowledge creation can include “mashups of data.” Ushahidi is an open source platform that facilitates crowdsourcing through the use of SMS/cellphones and online mapping. It has been used in disaster relief, for example, in Pakistan, and other scenarios from London Tube strike to election monitoring to mapping crime incidents Atlanta.

(2) Crowd Creation

Crowds create original works of knowledge or art. The Royal Opera used Twitter to crowdsource a new opera. They encouraged Twitter users to send suggestions for the plot. The opera staff collected the suggestions and summarized them on their blog. Opera is not the only art form, there’s been crowdsourced choreography – Dance Theatre Workshop. Each week they asked their Twitter followers to contribute a movement and then the company performed them and posted a video on YouTube. And, a symphony orchestra, made headlines when they crowdsourced musician auditions for the Youtube Symphony orchestra.

How do you measure the impact of the crowd here? Does being engaged in the creation of the work spur more appreciation for the art form and hopefully attention and participation? Does crowdsourced creativity reach a different (younger) and new audience segment? While it is probably difficult to absolutely prove cause and effect, implementing a crowd artistic creation requires a discussion about letting go of control or at least being explicit about how creative contributions will be accepted or curated or added to the work. Do you accept everything or is there curation?

(3) Crowd Voting

The crowd votes, rates, or gives feedback and tips on ideas, products, places, and even people. Internet platforms make it is easy for crowds to vote, rate, and provide feedback. Think Yelp, eBay, or Amazon.

Crowd voting has been used in Cause Marketing. There has been an explosion of “Vote for Me” contests that have become contests in techniques for vote getting and inspired cause fatigue at worst. At their best, they spread the awareness of a commercial brand and provide an opportunity for small nonprofits that don’t typically receive large amounts of funding to win dollars.

Crowd sourced philanthropy, on the other hand, does not typically select the best idea or project to fund by popular vote. Many foundations have taken a hybrid approach, acknowledging a role and place for expertise in addressing a “wicked problem” or spurring innovation. Hybrids include a mix of openness and curated decision-making by experts. The design might include a sequence of:

– Open call for submissions, public vote/commenting and a group expertise select the finalists

– Open call for submissions, experts select a smaller group of finalists, public vote/commenting to select winners

How to structure crowd sourced philanthropy based on voting or feedback depends on the outcomes of the project, a theory of change. The Knight Foundation’s News Challenge, Case Foundation’s Make It Your Own awards, and Island Collaboration Fund are examples of the hybrid process and linked to a clear theory of change. Key in the implementation is being clear and transparent about how funding decisions will be awarded. An impact question is – “How innovative are the ideas as a result of using a crowdsourcing process?”

Voting, rating, and feedback crowdsourcing projects have applications beyond philanthropy and marketing. It can help organizations make a traditionally closed process more transparent and ultimately improve the level of feedback. Conferences have taken this approach to shaping their agenda. NTEN used a hybrid crowdsourcing approach to solicit panel proposals for its NTC 2011, similar in design and approach to the method SXSW has used. Looking at impact is a question of how the crowdsourcing broadened the diversity panelists and topics as well as how this approach increase awareness and registrations for the conference. And, reaping that value also depends on using an efficient way to crowdsource the decision.

Brooklyn Museum implemented a crowdsourced photography exhibit experiment called “Click! A Crowd-Curated Exhibition.” Using a hybrid approach, there was an open call for photographs that attracted 389 entries. The entries were ranked by 3,444 people, including both general public, museum goers, and expert curators. You can compare the ratings by level of expertise. One of the surprises, was that the sverage amount of time that people looked at the online images was 22 seconds – compared to in-person in exhibit studies that found 6 seconds. Measuring impact is how did the crowdsourcing process attract a more diverse selection of art works, but also how it might have encouraged more people to appreciate the works.

Next Step Design is an experiment in “Crowdsourcing Public Participation in Transit Planning.” Traditionally, government agencies ask for public input on planning projects by holding open meetings and workshops. The purpose of this project was to get this public input in a different way: online. Did the use of crowdsourcing enable them to get more and more in-depth feedback compared to the traditional method? Was it more efficient?

(4) Crowd Funding

This category taps the collective purse, encouraging groups to fund an effort that benefits many people. The idea is to leverage the funds of the crowd to complete a project they support. For the funders side, we looked at the America’s Giving Challenge from the Case Foundation. Impact measures not only looking at the total amount raised, but also the adoption of new online social fundraising tools which was a key objective.

There are a variety of platforms for crowd funding, including Causes, Crowdrise, Razoo, GiveZooks and others.

Crowdsourcing Resources

Crowdsourcing 101 by Beth Kanter

Some Truths About Crowdsourcing by Geoff Livingston

Social Good Crowdsourcing by Geoff Livingston

Crowds Can Not Be Trained Like Seals by Beth Kanter

How Does Your Nonprofit Work With Crowds by Beth Kanter

My takeaways from the discussion: A big takeaway for me was that you have to very clear and intentional about what you want the crowd to do – and your design has to facilitate the crowd’s work as efficiently as possible. A lot has to do with the technology platforms and how well it automates some of the crowdsourcing work flow.

- If you have implemented a crowdsourcing strategy, how have you measured impact? How do make it efficient so it returns the most value?

- Are there other examples of crowdsourcing in the nonprofit or philanthropy or cause marketing sector that fall into these categories? How did they measure impact? What worked in terms of the design?

Update: